|

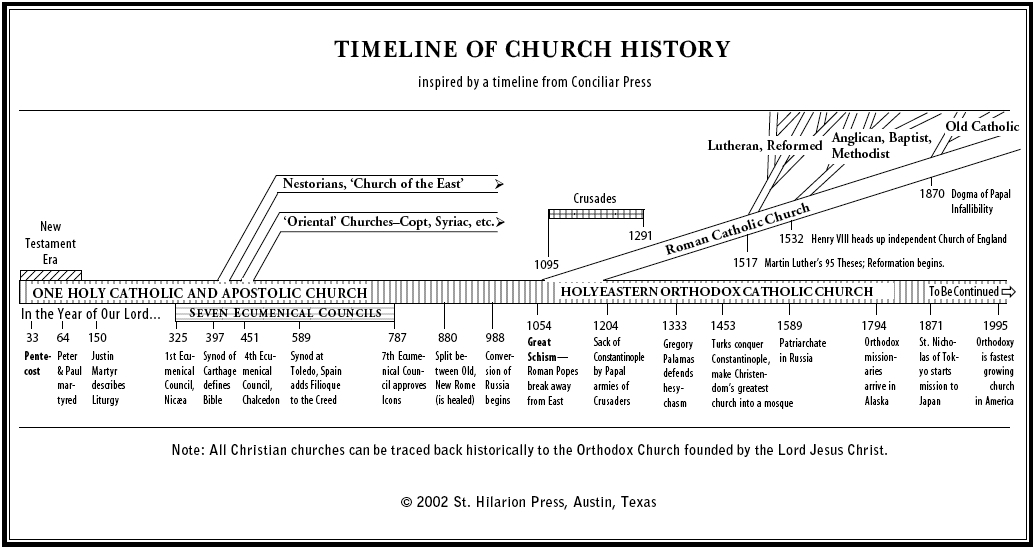

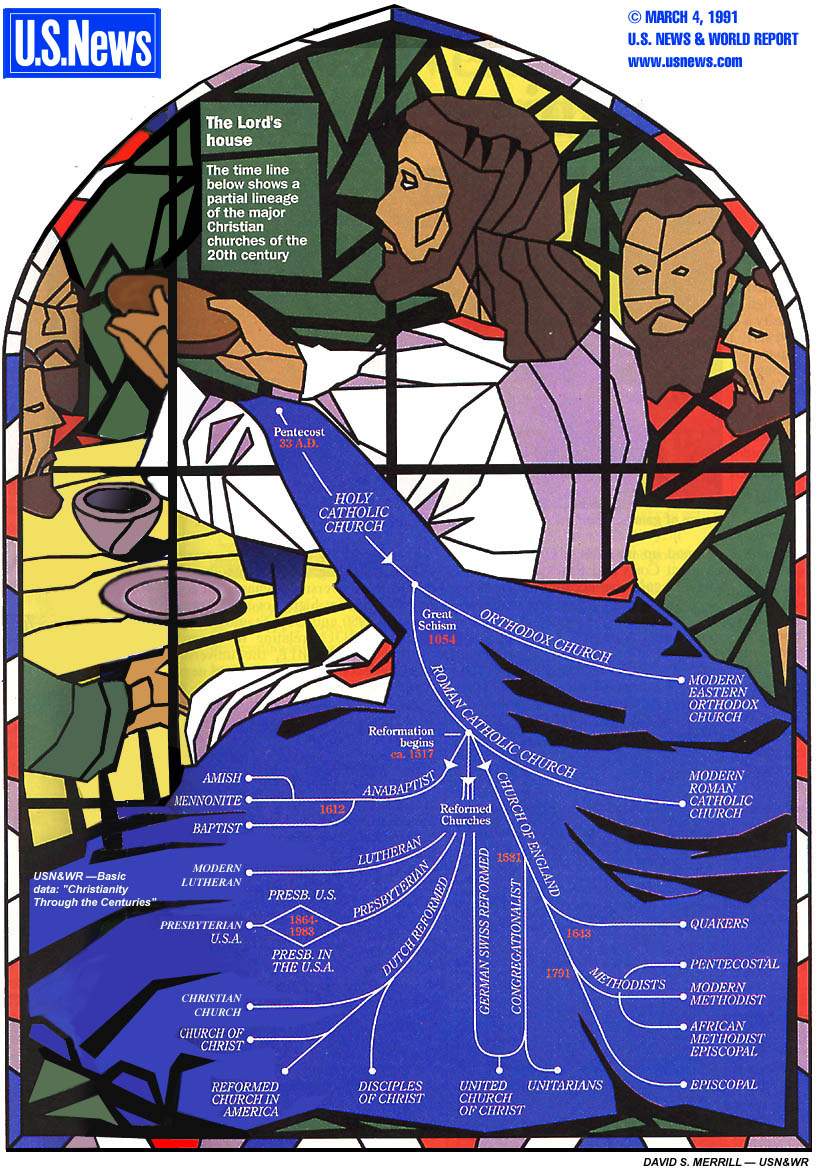

An Introduction to the “Orthodox Church” The Orthodox Church was founded by our Lord Jesus Christ. It is the Body of Christ (cf. 1 Corinthians 12:12, 27). It is the living manifestation of His presence in the history of the mankind. The most conspicuous characteristics of Orthodox Christianity are its faithfulness to the Apostolic tradition and its rich liturgical life. Orthodox Christians believe that their Church has preserved the tradition and continuity of the ancient Church in its fullness. It is a simple objective, or academic, fact that the Orthodox Church today maintains and continues the faith and practices of first-millennium Christianity. It is also an objective reality that the Roman Catholic Church and Her Protestant denominations departed from that common tradition of the Church of the first ten centuries. This simple, straightforward reality is why the Roman Catholic Church in its Second Vatican Council Decree On Ecumenism, Unitatis Redintegratio, describes the Orthodox Church under the sub-heading, The Special Consideration of the Eastern Churches, and states, “These (Orthodox) Churches, although separated from us, possess true sacraments, above all by Apostolic succession, the priesthood and the Eucharist, whereby they are linked with us in closest intimacy. It cannot, of course, be stated any other way from the Roman Catholic perspective, because the Orthodox Church is the Roman Catholic Church of the first millennium of Christianity. Whether the changes in theology – especially in Christology, Soteriology, and Ecceklsiology – expressed by the Roman Catholic Church and even moreso by her Proterstsant denominations are “correct” or otherwise, is a matter of theological opinion and perspective. That these differ from the first thousand years of undivided Christianity, however, is objectively factual. The Orthodox Church in twenty-first century numbers approximately 300 million Christians worldwide who follow the faith and practices that were defined by the first seven Ecumenical Councils. The word “orthodox” (“right belief and right worship”) has traditionally been used, in the Greek-speaking Christian world, to designate communities, or individuals, who preserved the unchanged faith (as defined by those councils), as opposed to those who professed new and/or different doctrines and were declared heretical. The official designation of the Church in its liturgical and canonical texts is “the Orthodox Catholic Church” (in Greek καθολικός, catholicos, which means “general” or “universal”). The Orthodox Church is a family of “autocephalous” (self-governing) Churches, preserving the first millennium ecclesiology of Christianity. The Roman Catholic Church differs from the earlier model of governance and is a centralized organization headed by a universal pontiff (pope). The Anglican Communion more closely resembles the organization of Orthodox Church as a “worldwide communion of churches.” The unity of the Orthodox Church is manifested in the universal confession of a common faith and through communion in the Sacraments. Not having a pontiff, the Orthodox regard no one but Christ Himself as the real head of the Church. The number of autocephalous Churches has varied throughout history, and Rome was once one of these. Today there are fourteen Churches: the four patriarchal Churches of Constantinople (referred to in Turkish as “Istanbul”), Alexandria (in Egypt), Antioch (with its See in Damascus, Syria), and Jerusalem, as well as the ten national Churches of Russia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Georgia, Cyprus, Greece, Poland, Albania and the Czech and Slovak Republics There are also “autonomous” churches which retain a canonical dependence upon one of the above-mentioned mother autocephalous Churches: Sinai, Crete, Finland, and Ukraine. In addition within the large Orthodox Diaspora scattered all over the world and administratively divided among various jurisdictions there are ecclesiastical “Eparchies” (provinces) dependent on one of the above-mentioned autocephalous Churches. The archbishop of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, is referred to as the “Ecumenical (οἰκουμενικό, which means “global” or “universal”) Patriarch of Constantinople,” holds titular or honorary primacy as primus inter pares (Latin for “first among equals”). The order of precedence in which the autocephalous churches are listed does not reflect their actual influence or numerical importance. The Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch, for example, present only shadows of their past glory. Yet there remains a consensus that Constantinople’s primacy of honor, recognized by the ancient canons because it was the capital of the ancient Byzantine empire, should remain as a symbol and tool of church unity and cooperation. Modern pan-Orthodox conferences were thus convoked by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Several of the autocephalous churches are de facto national churches, by far the largest being the Russian Church It is not the criterion of nationality, however, but rather the territorial principle that is the norm of organization in the Orthodox Church. In the wider theological sense “Orthodoxy is not merely an earthly organization which is headed by patriarchs, bishops and priests who hold the ministry in a Church which officially is called “Orthodox.” Rather, Orthodoxy is the mystical “Body of Christ,” the Head of which is Christ Himself (cf. Ephesians 1:22-23 and Colossians 1:18, 24 et seq.). The composition of the Church includes not only priests but all who truly believe in Christ, who have entered into the Church He founded in a lawful way through Holy Baptism, those who are living upon the earth and those who have died in the Faith and in piety. The Great Schism between the Eastern and the Western Church (nominally dated as occurring in AD 1054) was the culmination of a gradual process of estrangement between the east and west that began in the first centuries of the Christian Era and continued through the Middle Ages. Linguistic and cultural differences, as well as political events, contributed to the estrangement. From the 4th to the 11th century, Constantinople, the center of Eastern Christianity, was also the capital of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire, while Rome, after the barbarian invasions, fell under the influence of the Holy Roman Empire of the West, a political rival. Theology in the West remained under the influence of Saint Augustine of Hippo (AD 354-430) and gradually lost its immediate contact with the rich theological tradition of the Christian East. Most significantly, the Roman See was almost completely overtaken by the Franks who also began reformulating the theology of Western Christendom. Concurrently, the Orthodox East was increasingly subjugated by the followers of Islam which, while making life very difficult, allowed the Orthodox Church to fervently and faithfully maintain its theology unchanged and unaffected. Theological differences could possibly have been settled if there had not been two different concepts of church authority. On the one hand, the concept of a Roman primacy developed, based on the concept of the Apostolic origin of the Church of Rome which claimed not only titular but also jurisdictional authority above other churches, and was incompatible with the traditional ecclesiology of the historical Christian Church. On the other hand, the Eastern Christians considered all churches as sister churches and understood the primacy of the Roman bishop only as primus inter pares among his brother bishops. For the East, the highest authority in settling doctrinal disputes could by no means be the authority of a single Church or a single bishop but an Ecumenical Council of all sister churches. Over the course of time the Church of Rome also adopted various new doctrines, and even proclaimed certain new dogmas, which were not part of the Tradition of the undivided Christian Church of the first millennium. The Protestant Reformation of the fifteenth century further fractured Western Christian theology and ecclesiology, to the extent that at the beginning of the twenty-first century there are estimated to be over 30,000 independent Protestant denominations. The Roman Catholic proclamation by Pius IX in 1870 of papal infallibility as dogma, further widened the ecclesiological differences between the Christian East and West. The Protestant communities which split from Rome have also diverged significantly from the Christological and soteriological teaching of the Holy Fathers and the Holy Ecumenical Councils of the first millennium. Due to all of these serious dogmatic differences, the Orthodox Church cannot be in communion with the Roman Catholic Church and/or her Protestant denominations. Some very conservative Orthodox hierarchs (bishops) and theologians do not recognize the ecclesial and salvific character of these Western churches at all. Some more liberal ones accept that the Holy Spirit acts to a certain degree within these communities although they do not possess the fullness of grace and spiritual gifts as does the Orthodox Church. Many serious Orthodox theologians are of the opinion that between the Orthodox Church and the heterodox confessions – especially in the spheres of spiritual experience, the understanding of God, and salvation – there exists an ontological difference which cannot be simply ascribed to cultural and intellectual estrangement of the East and West but which is a direct consequence of a gradual abandonment of the sacred tradition by heterodox Christians. At the time of the Schism of AD 1054 between Rome and Constantinople, the membership of the Eastern Orthodox Church was spread throughout the Middle East, the Balkans, and Russia, with its center in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, which was also called New Rome. The vicissitudes of history have greatly modified the internal structures of the Orthodox Church, but, even today, the bulk of its members live in these same geographic areas. Missionary expansion toward Asia and emigration toward the West, however, have helped to maintain the importance of Orthodoxy worldwide. Today, the Orthodox Church is present almost everywhere in the world and is bearing witness of true, Apostolic and patristic tradition to all peoples. The Orthodox Church is well known for its developed monasticism. The uninterrupted monastic tradition of Orthodox Christianity can be traced from the Egyptian desert monasteries of the 3rd and 4th centuries. Soon monasticism had spread all over the Mediterranean basin and Europe: in Palestine, Syria, Cappadocia, Gaul, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and the Slavic countries. Monasticism has always been a beacon of Orthodoxy which has made, and continues to make, a strong and lasting impact on Orthodox spirituality. The Orthodox Church today is an invaluable treasury of the rich liturgical tradition handed down from the earliest centuries of Christianity. The sense of the sacred, the beauty and grandeur of the Orthodox Divine Liturgy, make the presence of heaven on earth alive, experiential, and intensive. Orthodox Church art and music has a very functional role in the liturgical life and helps even the five bodily senses participate in, and experience, the spiritual grandeur of the Lord’s mysteries. Orthodox icons are not simply beautiful works of art which have certain aesthetic and didactic functions. They are primarily the means through which we experience the reality of the Heavenly Kingdom on earth. The holy icons enshrine the immeasurable depth of the mystery of Christ’s incarnation in defense of which thousands of martyrs sacrificed their lives. |