|

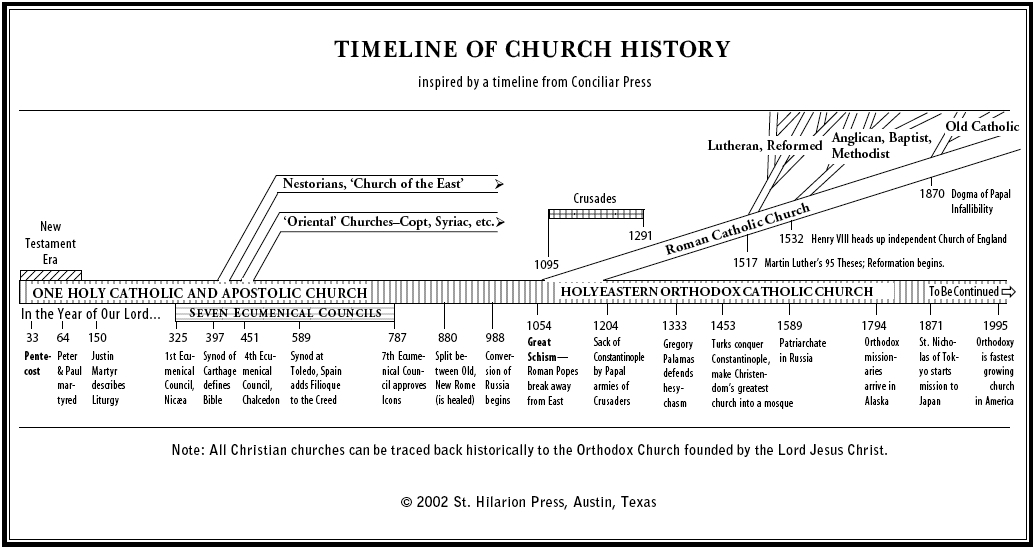

The Great Schism The Great Schism between the Eastern and the Western Church (nominally dated as occurring in AD 1054) was the culmination of a gradual process of estrangement between the east and west that began in the first centuries of the Christian Era and continued through the Middle Ages. Linguistic and cultural differences, as well as political events, contributed to the estrangement.

From the 4th to the 11th century, Constantinople, the center of Eastern Christianity, was also the capital of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire, while Rome, after the barbarian invasions, fell under the influence of the Holy Roman Empire of the West, a political rival. Theology in the West remained under the influence of Saint Augustine of Hippo (AD 354-430) and gradually lost its immediate contact with the rich theological tradition of the Christian East. Most significantly, the Roman See was almost completely overtaken by the Franks who also began reformulating the theology of Western Christendom. Concurrently, the Orthodox East was increasingly subjugated by the followers of Islam which, while making life very difficult, allowed the Orthodox Church to fervently and faithfully maintain its theology unchanged and unaffected. Theological differences might possibly have been settled if there had not been two different concepts of church authority. On the one hand, the concept of a Roman primacy developed, based on the concept of the Apostolic origin of the Church of Rome which claimed not only titular but also jurisdictional authority above other churches, and was incompatible with the traditional ecclesiology of the historical Christian Church. On the other hand, the Eastern Christians considered all churches as sister churches and understood the primacy of the Roman bishop only as primus inter pares among his brother bishops. For the East, the highest authority in settling doctrinal disputes could by no means be the authority of a single Church or a single bishop but an Ecumenical Council of all sister churches. Over the course of time the Church of Rome also adopted various new doctrines, and even proclaimed certain new dogmas, which were not part of the Tradition of the undivided Christian Church of the first millennium. The Protestant Reformation of the fifteenth century further fractured Western Christian theology and ecclesiology, to the extent that at the beginning of the twenty-first century there are estimated to be over 30,000 independent Protestant denominations. The Roman Catholic proclamation by Pius IX in 1870 of papal infallibility as dogma, further widened the ecclesiological differences between the Christian East and West. The Protestant communities which split from Rome have also diverged significantly from the Christological and soteriological teaching of the Holy Fathers and the Holy Ecumenical Councils of the first millennium. Due to all of these serious dogmatic differences, the Orthodox Church cannot be in communion with the Roman Catholic Church and/or her Protestant denominations.

|